Stagecoach (1939)

John Ford’s ‘Stagecoach’

To understand the themes of "Stagecoach," it might be helpful to understand 18th century philosopher John Locke's "Tabula Rasa," or "Blank Slate." In this thought experiment, a group of individuals are removed from society and placed on a 'blank slate.' From there, they must form a makeshift society unrestrained from any previous social conventions. The society they create must then come from an internal set of values and morality, unbiased from any proceeding notions. With "Stagecoach," individuals perform this experiment, as they vacate their safe, yet conceited civilized world and band together to form a makeshift society in order to survive. With this, they must abandon their social identities and form a social construct from within themselves.

The way Ford directs the film draws inspiration from his silent picture roots. You could almost watch the film without sound and still get a general idea of the interplays at work. Much of the drama centers on the relationships between characters, as these relationships demonstrate the social constructs held within. So, how exactly does Ford demonstrate these dynamics leaning on wordless, action-oriented association? Through 'the space between,' we are able to build an internal framework - done by examining the reactions of characters to their situations and to each other. Like with a silent film, interpolating facial expressions can provide meaningful internality, as often times words can prove frivolous. The entire film can be seen as a series of 'reaction shots,' showcasing the unspoken social dynamics at play.

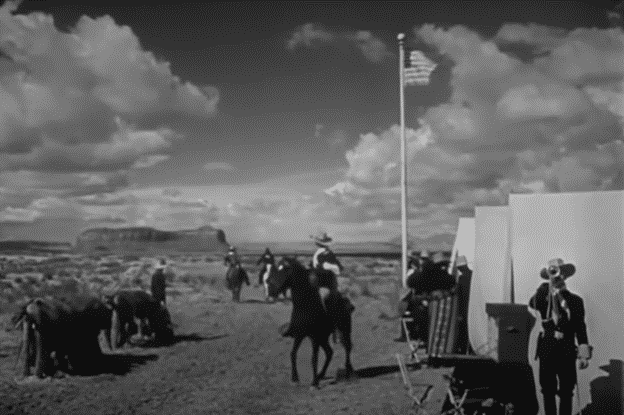

The film begins with a shot of the great desert plains of the Old West, a venue we will come to be intimately familiar with. The soldiers ride up on horseback to a military outpost to warn of raids by Apaches. Ford presents a shot of the camp, bugle blowing, and the American flag firmly raised. This presents us with the initial notion of society in this piece - America. Ford then takes us into a typical 19th century Western American town, providing a tracking shot of the hustle and bustle of the locale. This is our society.

The first characters Ford introduces us to are the high-borns. After all, with 'society' comes class dynamics. Lucy, an upper-class lady of respectability, is deciding to take a stagecoach to meet her military commander husband at a nearby outpost. She runs into a well-dressed man named Hatfield, as the two share a meaningful glance. The other elitist women tell Lucy not to engage with him, as he is a degenerate gambler. This is the first noticeable 'label' placed on a character. The next elitist character we come across is the respectable town banker. While Ford makes a point to subvert our expectations about the other characters rather slowly, he has no trouble identifying the banker as a corrupt person, without any respect whatsoever. He does this by providing a close-up of the banker looking solemnly suspicious after receiving funds from one of the local high-class women. He then suspiciously places the money in an unmarked bag. Ford's quick revelation about the true nature of this staple of society perhaps had something to do with the national temperament towards the banks in 1939. After the economic collapse ten years prior, the surging distrust of these high-brow profiles was all too palpable.

The next group of characters we meet are the social outcasts. We are shown a woman, Dallas, being escorted to the stagecoach by a handful of snotty elitist women. Through hinted context, we learn that Dallas is a prostitute who is being thrown out of town for her debauchery. Another person being thrown out of town is Doc, the town doctor. He is being stripped of his practice for his incessant alcoholism, now no longer a reliable, steady presence. The debased treatment by Dallas and Doc are spotted elements of social prejudice, as society has now labeled and branded them as unworthy characters who can no longer intermingle in a 'civilized' world.

Along for the ride with Lucy, Doc, Dallas, and the banker are a whiskey salesman named Mr. Peacock, the stagecoach driver and simpleton, Buck, the marshal escorting them named Curly, and the previously mentioned gambler Hatfield, who decides to join the party to protect the respected Lucy after the group learns of Apache raids nearby. This ragtag group will set out on their perilous journey, going out into the blank slate of the American West. These cliched architypes demonstrate the foundation of our national character. In removing these 'labeled' individuals from their familiar constructs, we see them on a path of self-discovery, and a path to uncover their social blindness. Ford presents us the below shot to demonstrate the leaving of a comfortably enclosed civilization, as the stagecoach moves past the resolute fences of the modern world, pointing headlong into the vast wilderness of the unknown.

While riding through the Western terrain, Ford introduces us to the last character joining our group. The reason for the marshal's accompaniment is due to the notion that he could capture Ringo Kid, the notorious outlaw. Ringo is out for vengeance for the murder of his family and has been wreacking havoc ever since. Even though we have not met him until this point, we have heard about the kind of problems he could cause the group if there was ever a run-in. However, Ford keeps in line with the theme of subverted expectations by introducing Ringo in a 'hero shot.' As the group make their way along, the stagecoach comes to a screeching halt as we hear the outlaw call out. Just then, a dolly shot goes into a rapid push-in on a close-up. This splashy entrance makes the John Wayne character appear larger than life on screen, defining his heroism visually. This 'hero zoom' is quite unexpected for a character who has largely been vilified throughout the beginning of the film and suggests that our assumptions about this person we don't know is simply that, an assumption. This adds to the preconceived pretensions all the characters seem to share about each other. This is also the very first time John Wayne has been on screen in a John Ford film. Before this, John Wayne was only ever in B-picture films. However, "Stagecoach" skyrocketed him to national notoriety. Wayne and Ford would go on to make 14 films together. This shot was an ignition point for a historic collaboration.

Because Ringo is stranded by his lame horse, he accompanies the group by order of the marshal. Huddled in the claustrophobic stagecoach, petty differences begin to emerge. Differences in class come about through the banker and Lucy's sly pettiness. Differences in geography and allegiances emerge between Doc's allegiance to the Northern alliance while Hatfield associates with the Southern Confederacy. Differences in morality are demonstrated as well through Lucy, Hatfield, and the banker looking down on Dallas, Doc, and Ringo. These varied differences breed division and conflict amongst the passengers, as they are so associated with their societal identities that their empathy becomes limited. Their separations by class, geography, morals, manners, and allegiances all create a sense of detachment. This seems ironic, as the collectivism found within a societal group usually is associated with comradery. However, Ford demonstrates the opposite effect. Ford also belittles these squabbles by cutting from them to images of the harsh external terrains of Monument Valley, where he shot the film. This also presents a hint to the viewer about the impending need to overcome such benign disputes.

When the group arrive at Dry Fork, they learn that the expected cavalry has already departed to Apache Wells. Buck wants to turn back, but the decision is put to a vote - another reminder of the foundation of American society. They vote to proceed, even though the road ahead is perilous. As they settle into Dry Fork, we see more of their societal pretensions play out. Ford continues to film 'reaction shots.' As Lucy and Dallas sit at the dinner table, they exchange glances. Rather than show the glances via 'over the shoulder' subjectivity, Ford places the camera perpendicular to their eyeline. This removes a subjective connection to any one character. It would be very easy and tempting to assume Dallas's point of view, empathizing with her being looked down on. However, Ford's 'removed' camera asks the viewer to regard both stares equally. Not only is Dallas trapped by her regulated place at the bottom of the social latter, but Lucy is also trapped. Her delusions of high-class etiquette are so engrained with the fabric of social acceptability, that her perceptions allow her to belittle and dehumanize Dallas, unaware that her pretensions will come crashing down later. With this, Ford does not blame Lucy for her delusions. Rather, he blames social pretensions. After these harsh glances, Hatfield even asks Lucy if she would like to move to the other end of the table, closer to the drafty window. Hatfield's enabling of this social pretention further demonstrates that the problem is structural. Without ever expressing any of this through unnecessary dialogue, Ford is able to expertly capture how the characters view each other. The unflinching gaze of external reactions creates the internal scope necessary to understand the relationship structures present.

When the group gets to Apache Wells, they find that the cavalry has left here as well. Not only this, they learn that Lucy's husband has been wounded in battle and taken elsewhere for medical attention. Lucy faints and is taken inside to lie down. She begins to go into labor, much to the surprise to everyone, including the viewer. The birth of the baby presents a turning point in the film, as this provides the first opportunity to address a real life and death situation. Doc decides to abandon his societal vices and steps up to the plate to deliver the baby. When the baby is born, Lucy steps up to the plate by being a caregiver - staying up and taking care of the child in a moment of need. These two shedding their 'labels' allows them to re-establish their identities and re-prioritize their imminent values. John Ford said of the baby's birth, "The baby's birth is a crucial turning point. The headstrong young Mallory [Lucy], Louise Platt, was 24, has been impetuously pursuing the will of the wisp of being with her husband when her time comes. With her fall to the floor, that mirage disappears, and other illusions will be challenged by virtue of her class and temperaments. She can control events that she can imperil herself and her child without regard for her fellow travelers, that she is above and does not need lesser mortals." With Lucy lying in bed staring up at Dallas as she braids her hair, the staging by Ford prompts a reversal of positions. In the beginning, Lucy looked down (figuratively) at Dallas. Now that Dallas has proved herself as a matronly caregiver to Lucy's child, Lucy is forced (now literally) to look up to Dallas. Up until this point of the story, the views of the privileged dominate. However, the birth of the baby calls for a moment of crisis, and in bounding together to tackle it, democratization rules. It is now the outcasts and despised who will step up and set the tone.

After the birth, Ringo witnesses Dallas taking on matronly responsibility. Throughout their trek, Ringo has been either unaware or apathetic towards Dallas's lowered social standing. Because of this, he treats her like a human being, unlike the others. This connection furthers when he offers to run away with Dallas to a ranch he owns in Mexico. Her response is, "But you don't know me! You don't know who I am!" Dallas is unable to view herself outside of the lens of her societal label. This inability to see herself is one way Ford employs her (and everyone else's) basic character structure. The sense of self-identity lack any actual self-individualism and is only relied on one's place in the social hierarchy.

Ford's painterly vision as a director allows him to compose stillness and silence to illustrate romantic spaces. These spaces, whether it's the open epic-ness of the desert plains or the intimate interiors holding space between characters conveys palpable portraits of elevated intimacy. We tend to see shots of deep focus, which allows characters to blend in to their surroundings. For example, there are many shots that break vertical continuity, like being able to see ceilings behind the characters. Not only this, spaces at the forefront of the frame seem congruently focused with spaces further away. This enables the picture-esque quality of a painting, as paintings are never limited by depth of field. When Orson Welles was asked what directors he drew inspiration from, his response was, "I like the old masters. By which I mean John Ford, John Ford, and John Ford." In preparing to shoot "Citizen Kane," Welles claimed he watched "Stagecoach" over 40 times. This becomes all the more apparent with some of the low angle shots as well as the deep focus shots, like the one below.

Ringo and Dallas decide to abandon their toxic societies by running away together. However, before they can, the group is ambushed by Apaches. What follows is one of the most memorable action sequences in film history. The stagecoach rides through flat desert terrain as the armed group shoots away at the Apaches in hot pursuit. What makes this chase sequence so great is its standalone intensity. Up until this point, the film has been a morality play dealing in reaction shots and characters huddled together discussing their differences. Now, the thrill of danger and death is hurdling towards them. The average shot length for the chase sequence is 5 seconds, which is half the average shot length for the rest of the film. The effect is the same as with the Odessa Steps sequence in Sergei Eisenstein's "Battleship Potemkin." The quicker pace of the edits enhances the frantic chaos of the scene and builds exasperated tension. Not only this, Ford violates the 180 degree rule - the rule that requires continuity of action from shot to shot. Here, he reverses the direction the stagecoach and riders are moving in successive shots. This freedom of rule breaking allows Ford to break from convention for poetic exploration of action, rather than have realistic stylization. It also allows Ford to maintain the intensity of the chase. Another creative rule-break occurs when Ford places cameras on the ground, allowing the riders to ride over them. This also escalates the intensity by placing the viewer squarely in the action. The high energy, pace, and stunts elevate the scene to iconic levels, while providing a template for adrenalin-infused action sequences for decades to come.

Here, the action is moving from right to left, which then switches to:

Left to right.

Comments

Post a Comment